Behind the Scenes: Three Elements to an Impactful Story

Narrative storylines are one of the components of CyberRwanda, a digital health self-care platform that provides comprehensive sexuality education and access to contraceptive products for youth in Rwanda. They are also the feature that young people access the most on the platform. The storylines are series of teenage dramas, which follow characters as they deal with challenging situations revolving around their reproductive health. In reading these stories, you see characters go on behavior-change journeys, by the end of which they’ve been exposed to and adopt new behaviors like using condoms every time they have sex, getting tested often for HIV, and using other modern contraceptive options like emergency contraceptives and birth control pills.

For the most part, a typical story (be it a movie, a comic, or a book) is written to entertain. Behavior-change stories, on the other hand, are very intentional in how they are written and are meant to inspire some sort of action of change among those who read them. The CyberRwanda webcomics, in particular, are meant to shift norms among young people to increase the use of modern contraceptives, reduce unwanted pregnancies, and increase HIV testing.

It’s therefore not enough to sprinkle in a few moments of characters using condoms, getting tested for HIV, or practicing whatever behavior you want the audience to adopt. Doing this is no different from putting that information in a textbook or on a billboard, as has been done for years with little to no change to norms.

So the question is, how do you write these stories in a way that is impactful?

Engage Youth in the Process

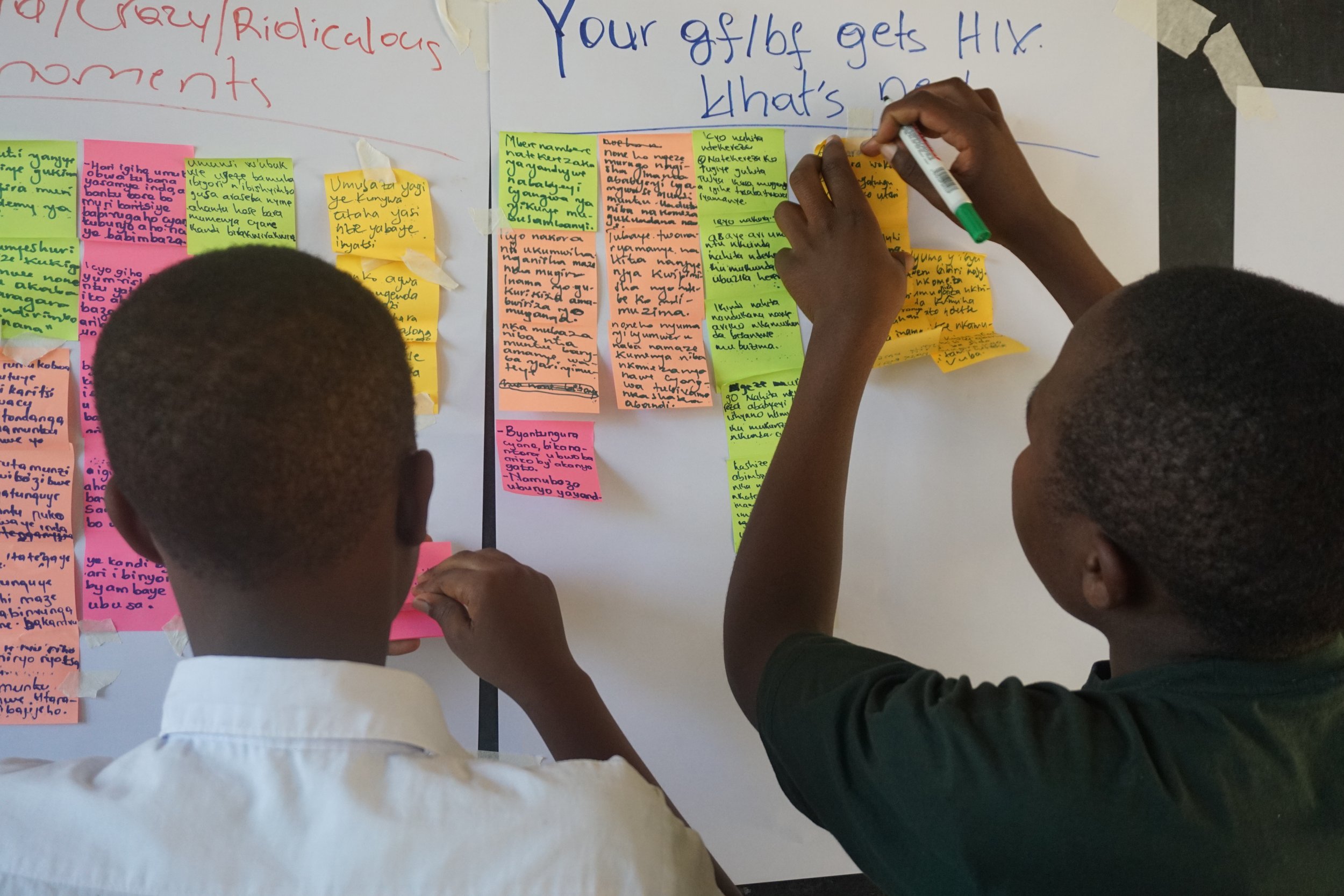

Youth validations and workshops, where I gather intel and test stories with youth, are at the core of the writing process. I host at least three of them, each with a different purpose (i.e. gathering data, structuring the story, or reviewing the story), depending on the stage I am at in the process. The feedback from these, is then used to create relatable characters who embody the experiences and realities of young people and portray what really matters to youth and how they respond to their environment.

In a youth validation workshop, you might find out that young people do not use condoms because they cannot negotiate with their partners to use them, they tend to have sex without planning to, or they just don’t know how to use them. It might also be due to other reasons you’ve never considered before. Speaking directly with young people gives you a better understanding of what they’re dealing with. You can then create a story that addresses those challenges, using characters that respond to those situations in different ways (ex: always carrying condoms, even when you don’t intend to have sex) and highlight why that solution is important.

Share Information Over Time

The CyberRwanda comics contain a lot of information around family planning, like condom use, birth control pills, IUDs, implants, and emergency contraception. Readers see characters using all these methods at one point. They will also notice, however, that the way these methods are revealed or when the characters use them is spread across seasons. This is very intentional.

A few years ago, when I first started writing behavior change stories, I made the mistake of showing all the methods very quickly and early on in the stories. What this does is make the stories sound more preachy and technical than realistic and natural. It also becomes too much for young people, because you’re trying to change a lot of behaviors in very little time. This ends up being confusing and is no different from the way information is often presented to young people.

For example, you would have characters first come to terms with using condoms, because that’s perhaps the easiest method to access. Then, you’d have them use emergency contraception as a back-up method in a particular situation. There is no formula to which comes first, but avoid presenting all options at once and too early on.

Structure Through Theme

As I mentioned above, the stories are very intentional, with a clear objective of shifting perception around an issue and encouraging a certain behavior change. To do so in a way that is natural and includes behavior change techniques, I structure the stories through themes.

Theme, in this case, is more than something abstract, like “friendship”; it’s an argument you want to make in your story through a character. This is otherwise known as a central dramatic argument, or a more active way of thinking about the main message you are trying to send the reader. An example of this can be, “Having HIV does not mean your life is over; you can still be in a relationship, have sex, and be happy.”

In the beginning of the story, the main character lives in ignorance of the central dramatic argument. As the story progresses, they encounter many barriers and live through experiences that work to bring them to a point where they can live in accordance with the central dramatic argument. This also presents you with an opportunity to tie in the central dramatic argument to other subjects along the way, like trust, friendship, etc. Following a central theme is effective, because the argument you are making isn’t being told but rather being shown through a character with which the reader empathizes.

Interested in our CyberRwanda project? Learn more!